Current Time.

A Quick Recap

In this series, I am sharing my conversations with my father and inviting you to be part of them. This new installment will focus on the pre-state period and the early days of Israel when the country faced the challenge of housing almost a million immigrants who arrived with nothing but the clothes they wore.

In this installment, we'll focus on the development of large-scale residential projects. We will look at how they were built, what made them possible, and how they shaped the lives of the people who lived in them.

This is a bonus episode. Let’s dive in.

Nissim: Today, we’re picking up where we left off in yesterday’s session, exploring what happened in the United States after World War II and through the 1950s and 1960s.

The American Dream

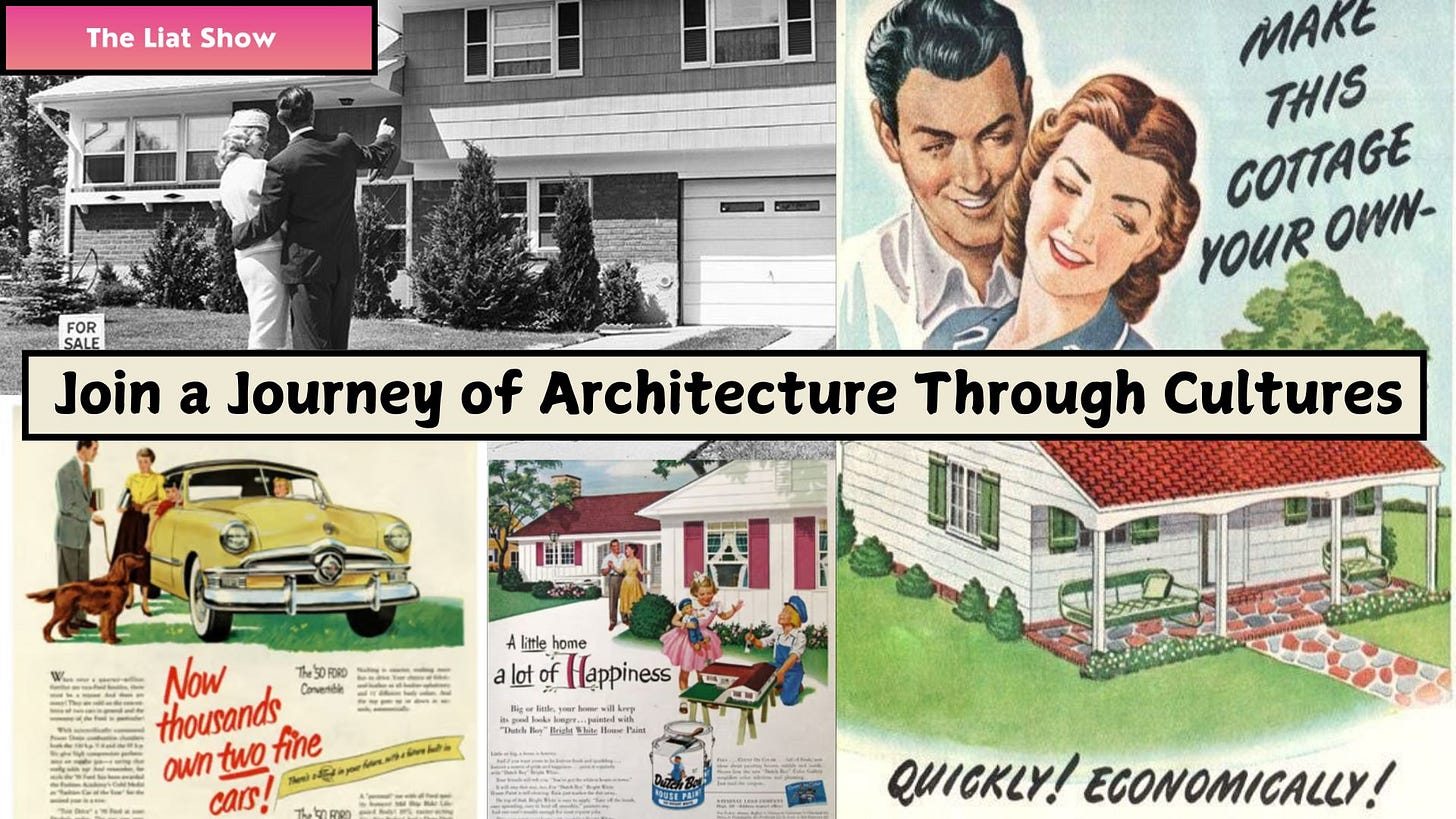

1945, the end of World War II. Millions of soldiers return home, and America faces a severe housing crisis. The government decided to release agricultural land for development cheaply and quickly. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) has started encouraging banks to give out loans and has lowered the required down payment.

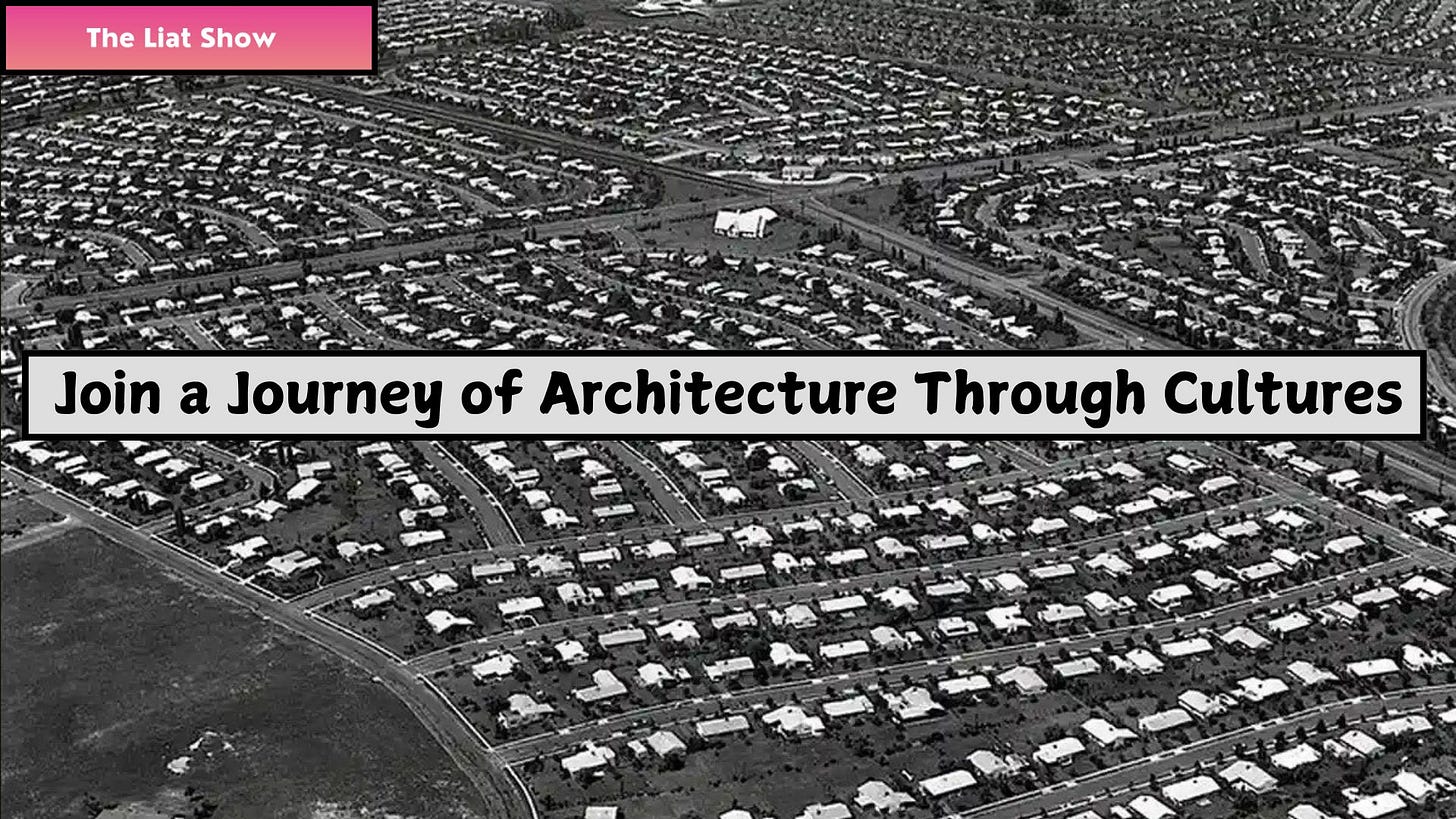

As a result, between 1945 and 1960, 13 million new housing units were built. Eighty-five percent of them were in the new suburbs. By 1960, 62 percent of American families owned a home.

Miles upon miles of single-family homes, in some cases exact replicas of each other. The American suburbs became the largest suburbanization project in the world. Suburban homes became a symbol of success and status. A big house, a green yard, space for kids, and most importantly, one or two cars in the driveway. This was the beginning of the American Dream.

The growth of the car industry that started in the 1950s made it suddenly possible to live outside the city center, even far away. In 1956, the federal government passed a law to build 66,000 kilometers of new highways. These factors amplified the dependency on cars, which led to the massive expansion of the car industry during the mid-to-late 20th century and the success of the suburban model.

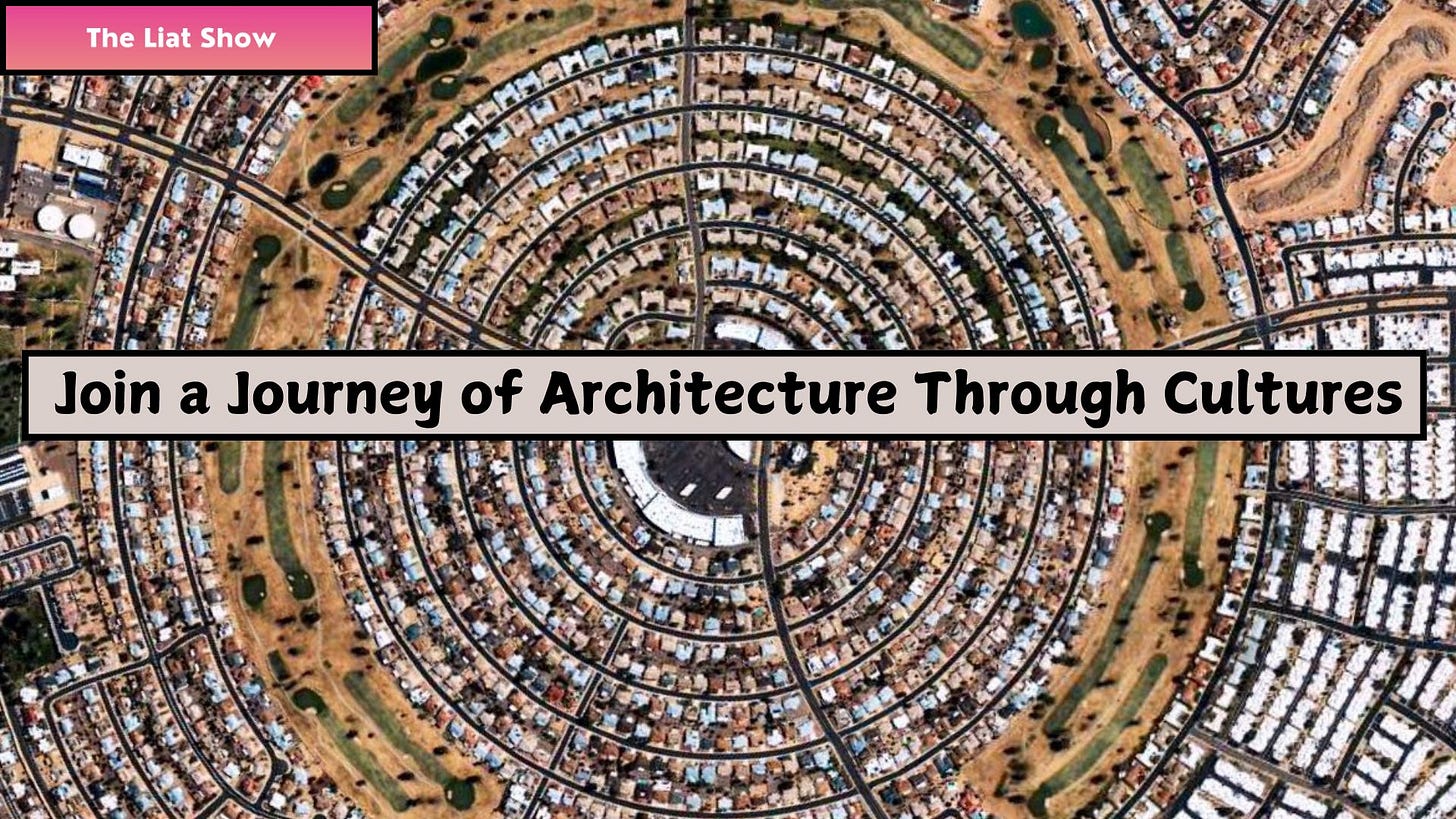

The result was massive suburban cities built alongside highways, completely dependent on cars, wide roads, traffic circles, outlet malls only accessible by car, and, of course, the famous drive-ins. Families realized they had to own a car if they wanted to live in the suburbs.

The American Dream of a big house, three kids, a dog, and two cars drew many people out of the cities into the suburbs, especially middle- and upper-class families who could afford it.

Exodus

This mass departure caused city centers to shrink, budgets to dry up, and crime to rise. This shift didn’t just lead to the decline of city centers. In some cases, to accommodate car-reliant suburban populations, downtown areas were radically transformed and replaced with massive interchanges and highways.

The suburbs, on the other hand, thrived and, in fact, still do. Many huge neighborhoods were built using the exact same model, essentially carbon copies of one another. It was practical, but lacked character and unique architectural design for the residents of these homes.

As of 2017, about 52 percent of U.S. households lived in suburbs, while 27 percent lived in cities and 21 percent in rural areas. That same year, suburban development grew by 15 percent, while city construction increased by only 5.7 percent.

Today, there is growing criticism of the suburban model. This car-based society is estimated to cost the U.S. economy significant financial costs due to time loss, inefficiency, and wasted land.

The American suburbs were born from optimism and a vision of peaceful, utopian living. But in reality, they come with economic, social, environmental, and psychological consequences, such as traffic jams. Suburban residents experience extensive daily driving, encompassing commutes, errands, and recreational activities.

Other people’s problems always look easier. However, the United States also faced problems with public housing projects in big cities, similar to the ones in Israel. For example, the Desire Projects in New Orleans, Louisiana, were built as public housing for the city’s underprivileged African American community. But from the very beginning, the living conditions were poor.

The project included around 262 two-story buildings with about 1,860 housing units, making it one of the most significant public housing projects in the U.S. It was built in a swampy, isolated area, surrounded by train tracks, industrial zones, and canals, which made daily life difficult for residents. Over the years, especially during the 1960s and 1980s, the area became known for high crime rates, with rising drug activity and violence. The Desire Projects became infamous for their harsh living conditions and widespread violence.

Liat: If the government’s approach is to provide housing in uninhabitable or extremely remote areas, then what is the surprise that public housing projects fail while suburban developments succeed? Sure, suburbs have their problems, but they’re far less severe than issues like crime and poverty.

Nissim: Driving might feel like a waste of time, but I don’t see it that way. This is a small price to pay when living on a big property with a backyard and a pool. People living in the suburbs can provide their kids with a good education and other activities while providing for their family. A hundred years ago, working hard meant physical labor. Today, working hard means commuting to work.

We are facing a similar housing crisis today, and the public needs to learn from history how to initiate projects and, at the same time, learn from the mistakes that resulted. The public needs to learn about the success factors of new communities, neighborhoods, residential buildings, and, on the other hand, the failures of projects and the causes for these failures. As you can notice, there are more failure factors that are caused by the geographical area, culture, employment, education, nature, pleasure, and accessibility to travel or public transportation than problems with the construction itself. Of course, we can see failures with construction methods and materials. However, these are easier to handle than changing people's behavior or their reaction to unemployment or the inability to get to a workplace using public transportation.

Liat: I want to teach that class. If I could gather all the people in the world who are unemployed, living in places unfit for human habitation, or crammed into overcrowded housing, and motivated to change their reality, I would teach them online the essential elements of what makes a livable home, a connected neighborhood, and a thriving town.

I'd teach them how to build based on their geographic location, local planning and construction laws in their area, what available materials they can use, and the kinds of innovations that could help them move forward faster.

We need to teach practical employment skills online through the lens of construction, urban renewal projects, and the creation of living environments.

Nissim: Don't you think people are already doing that?

Liat: No. All that exists online are piles upon piles of videos where mentors teach unemployed people how to become mentors themselves, but that’s not a job or employment or doing something for the environment you live in, and it's needed.

What no one has done at scale is exactly this! A global, accessible, practical curriculum that helps people build for their local conditions, using tools to adapt and innovate. Guide them online, watch their progress, and help them solve everyday problems remotely, no matter the conditions they live in. Help them work with the cards they have, using only online guidance.

Nissim: But how would you teach them? In some areas, people are so poor they barely have enough food to survive. On top of that, many aren’t educated, so they need to learn everything from scratch. To build, they need to understand concepts like engineering, how to work with space, or how to calculate the strength of a structure, for example.

You’d need a preschool to prepare them for the school of construction. And that is a massive headache. No one will come; people hate school. Now, even the US government wants to close schools.

The only way to succeed is not to tell them it's a school.

Liat: Like fight club.

Nissim: Fight Club? Do you want them to get into fights?

Liat: No. Like in the movie, where they’re not allowed to talk about Fight Club, and that’s exactly why it became so powerful. So let’s build this school the same way. We won’t call it a school. We won’t talk about it like it’s education. The three rules of our version of Fight Club.

You don’t call it school.

You don’t call it school.

If someone taps out, pauses, or disappears, we wait. No shame. No questions. No one gets left behind.

This isn’t school. This is how we build the future.

And the moment someone presses “subscribe,” they’re already in. They just don’t know it yet.

Please fasten your seatbelts and subscribe.

Unlock my potential to write the next great chapter in the most extraordinary story ever told. Your support would make a big difference in taking this journey to the next level.

Follow me on My Journey to Infinity to find out. It will be more beautiful than you could ever imagine.

Liat

In this journey, I weave together episodes from my life with the rich tapestry of Israeli culture through music, food, arts, entrepreneurship, fiction, and more. I write over the weekends and evenings and publish these episodes as they unfold, almost like a live performance.

Each episode is part of a set focused on a specific topic, though sometimes I release standalone episodes. A set is released over several days to make it easier for you to read during your busy workday. If one episode catches your attention, make sure to read the entire set to get the whole picture. Although these episodes are released in sets, you can read the entire newsletter from the beginning, as it flows smoothly, like music to your ears - or, in this case, your eyes.