Plans on Paper, Pain in Real Life: The Cost of Rushed Nation-Building

A Story Unfolding Across Timelines.

Current Time.

A Quick Recap

In this series, I am sharing my conversations with my father and inviting you to be part of them. This new installment will focus on the pre-state period and the early days of Israel when the country faced the challenge of housing almost a million immigrants who arrived with nothing but the clothes they wore.

In this installment, we'll focus on the development of large-scale residential projects. We will look at how they were built, what made them possible, and how they shaped the lives of the people who lived in them.

Ready? Let's dive in.

Liat: We ended the last session with the harsh economic reality during the 1950s, also known as austerity, Tzena in Hebrew.

Nissim: Indeed :) Austerity is an economic policy that is hard to understand in today's reality. People learn about it as part of history or economic studies, but in practice, it is almost impossible to explain the psychological impact of food budgeting when we have grocery store chains and almost every food item, from raw to processed, available on shelves nearly all year long. Austerity policies were implemented in many countries back then, so it wasn’t a unique policy at the time. However, the decade when austerity was implemented in Israel is remembered as a harsh time, and people still carry the emotional baggage of that era. Add to that the survivors of the Holocaust, and these psychological burdens have been passed down through generations.

Austerity in Israel

To understand the connection between housing and the economic policy of austerity, we must see the full picture. Everything had to be built at once. From 1949 to 1959, Israel implemented a policy of austerity, or Tzena. It was not an ideological choice but a necessary measure to prevent collapse. After the War of Independence, with a war-torn economy and a constant security threat, the new state was overwhelmed by refugees and immigrants who arrived with nothing.

At the first cabinet meeting of the elected government on April 26, 1949, it was decided to impose rationing. Ben-Gurion explained this as a temporary step dictated by the urgency of the situation.

The main reason was the mass immigration. Many of these new immigrants arrived destitute, from displaced persons camps in Europe or from Arab countries where they had been forced to leave everything behind. Israel had no foreign currency reserves. Prices for basic goods threatened to skyrocket due to supply shortages. If the market had been left alone, the rich might survive, but the poor would go hungry.

The government’s goal was to stabilize the economy and protect its people. Food, clothing, and consumer goods were rationed. Credit and investments were tightly managed. The aim was to save foreign currency and prevent inflation.

There were other motives too. The rising cost of living and the consumer price index needed to be controlled. And although people remembered the Tzena as a time of hardship, it worked. Food was available for all. Starvation was prevented. Inflation was reduced. And slowly, a foundation for a welfare state was laid.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Construction and Housing emerged as one of the most vital organs of the new state. Its job was to plan and oversee national construction. It created policies, led public housing efforts, and ensured that every building met the country’s new standards.

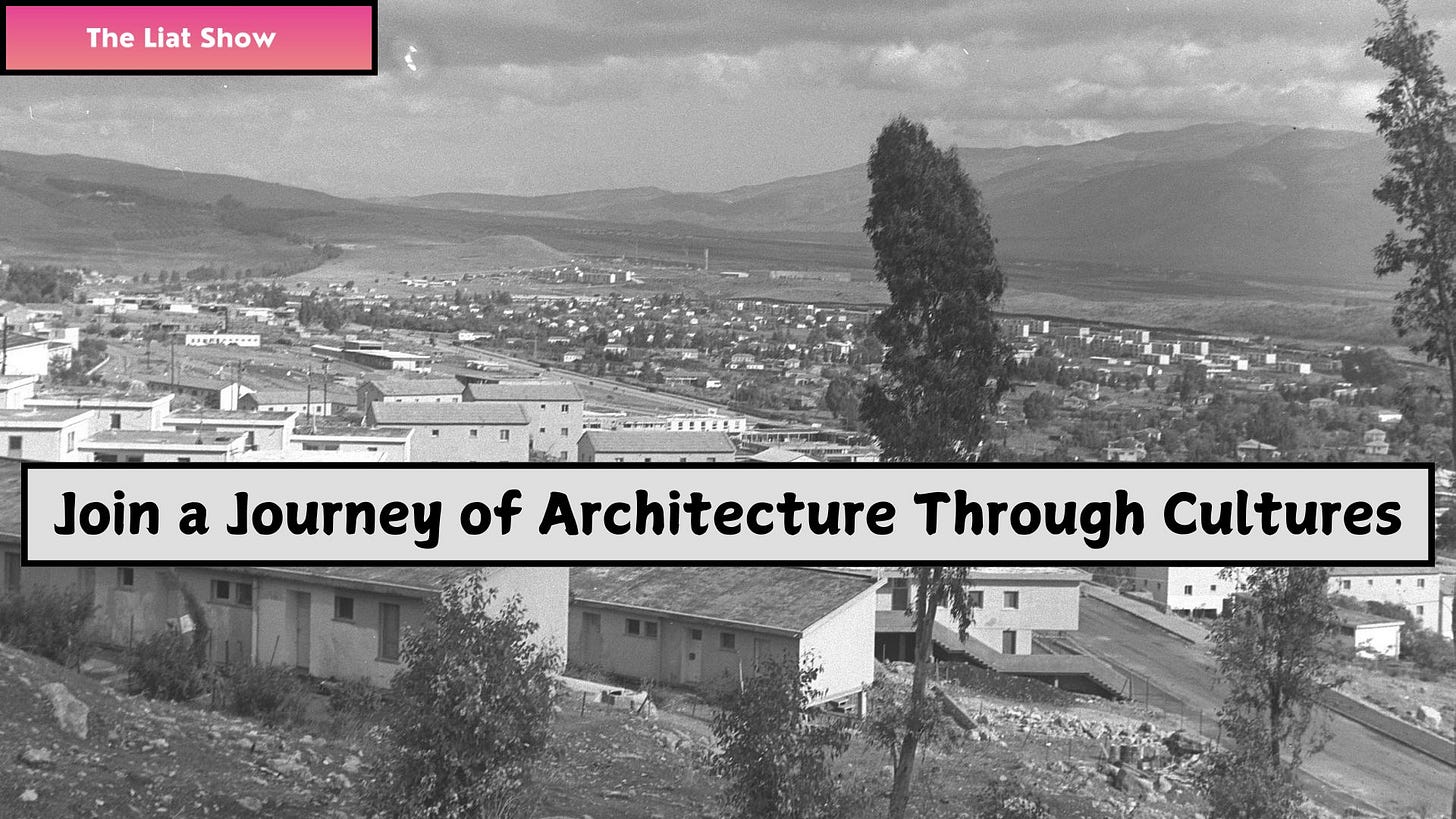

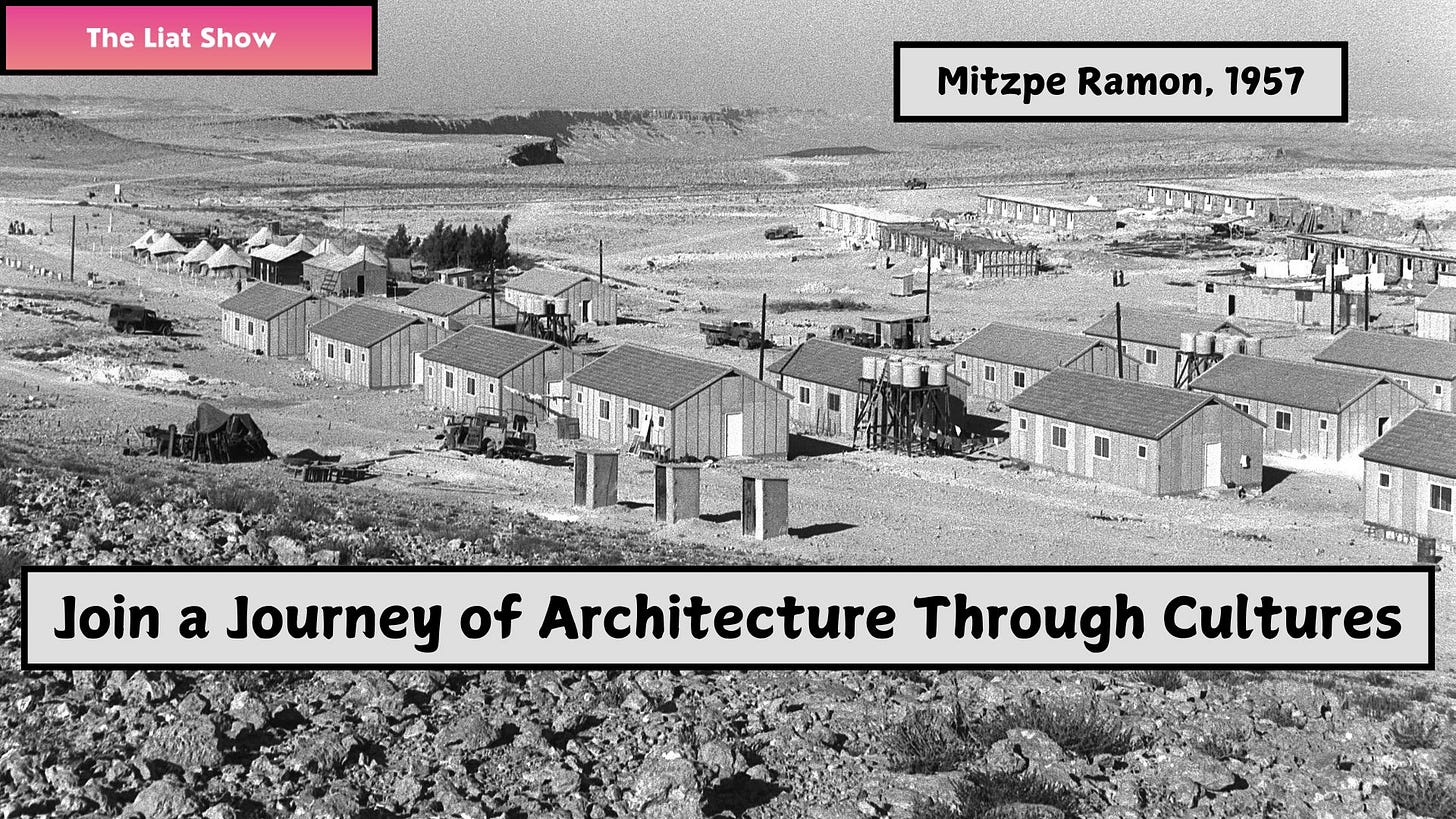

Housing remained the top priority. Immediate solutions included tents, followed by wooden huts with only basic bedrooms. Kitchens and bathrooms were outside. These were then replaced with permanent public housing in the late 1950s.

The Sharon Plan and Mass Construction

The nature of the ties between the veterans of the country and those from Europe and America helped the latter to use the veteran population, mainly relatives, to leave the transit camps. The difficult living conditions in the Maabarot took a heavy toll, especially in the isolated transit camps. Among the residents of these Maabarot, a particularly strong sense of resentment developed, which contributed to a social rift between the immigrants from Islamic countries, who were the majority of the transit camp population, and the European immigrants.

The young country faced severe economic and infrastructure shortages. The economic hardships worsened the situation because the government had to allocate enormous budgets for security, education, and basic infrastructure, leaving limited resources for public housing.

Moreover, due to the economic blockade and the wars that erupted in Israel’s early years, there was a severe shortage of building materials such as iron, wood, and cement. This situation required creative solutions.

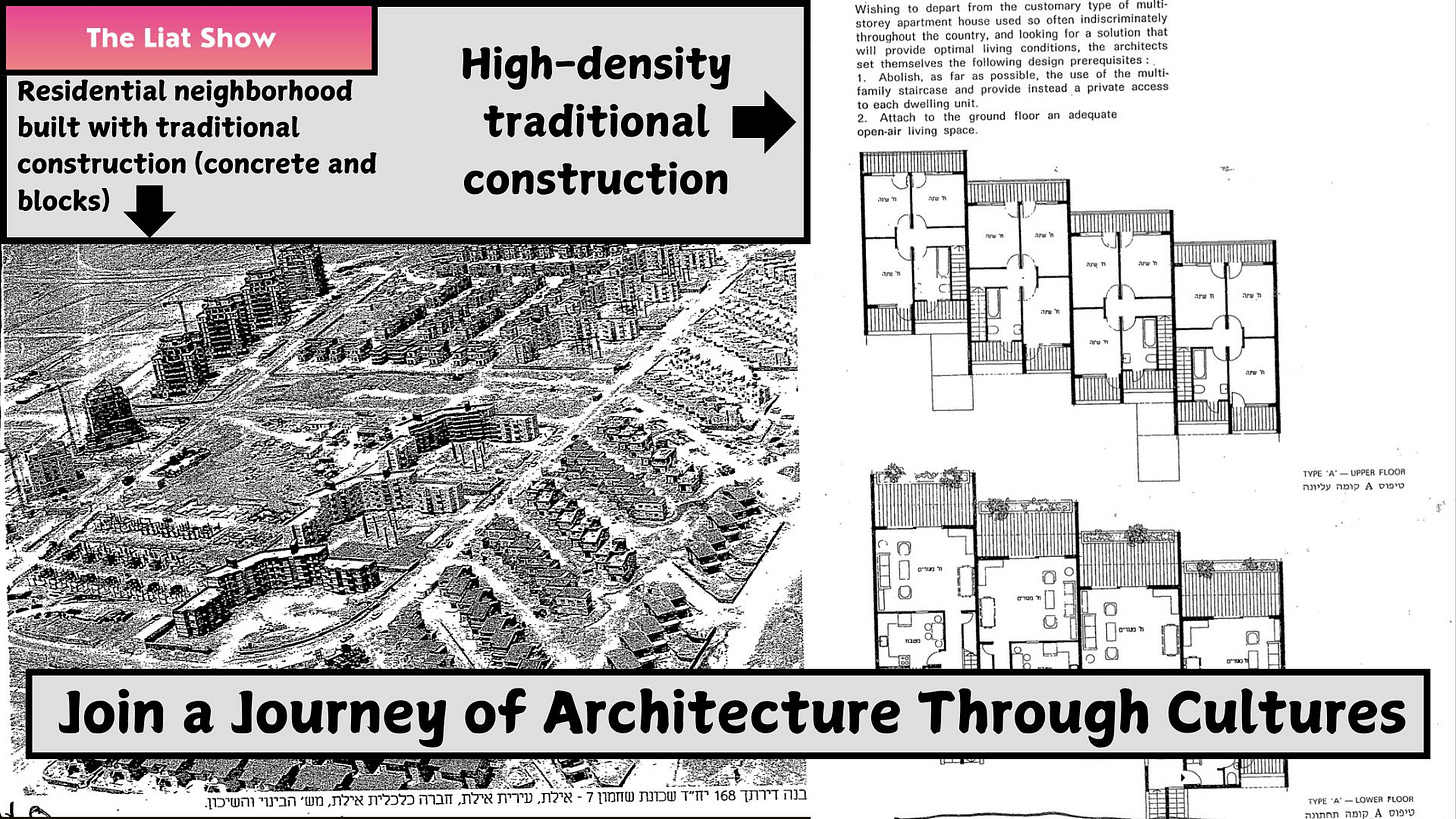

Facing a national housing crisis, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion turned to architect Arieh Sharon and asked him to design Israel’s first national zoning plan. The result was the Sharon Plan. It was ambitious, sweeping, and focused on the rapid construction of development towns across the Negev and the Galilee.

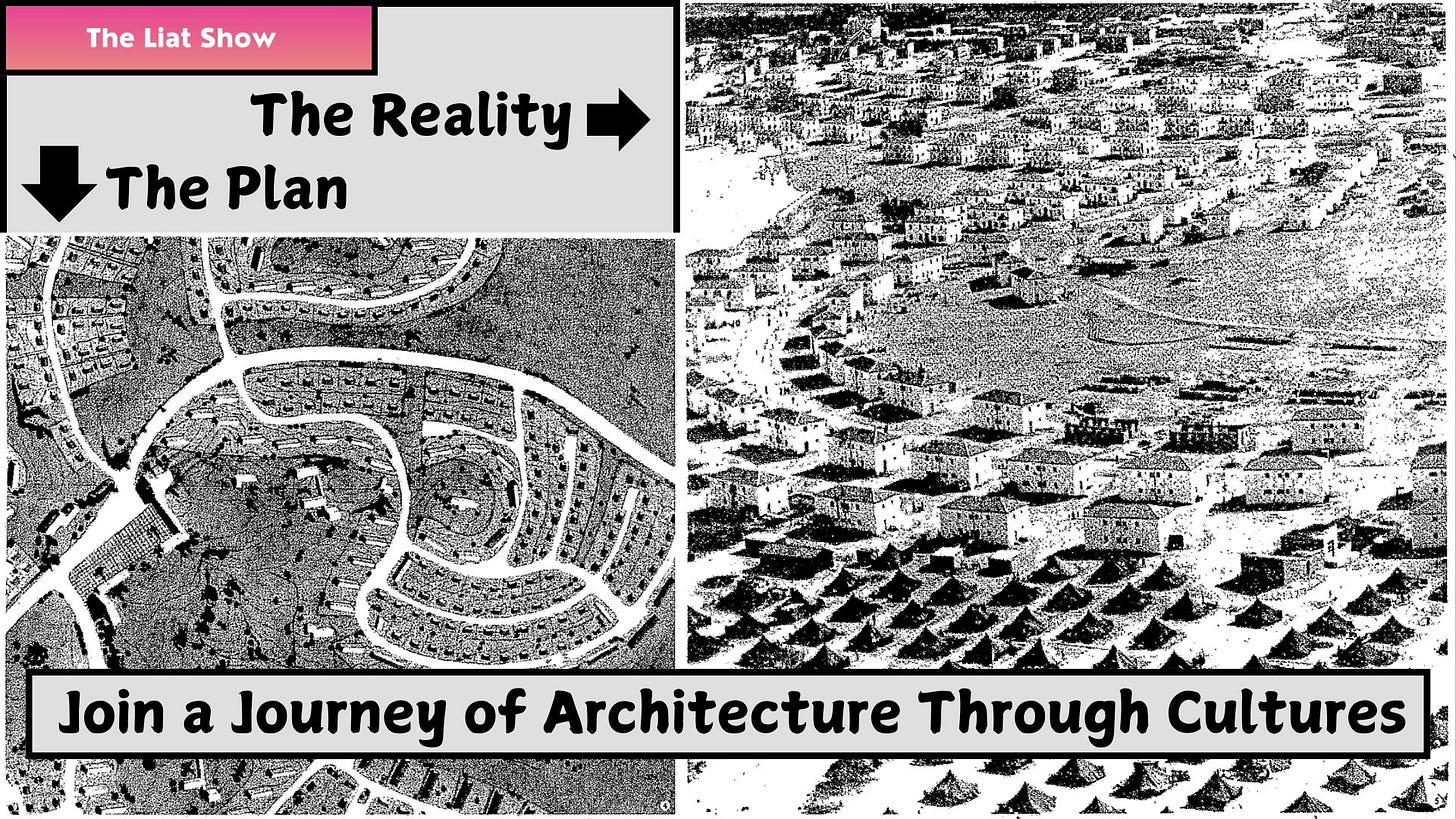

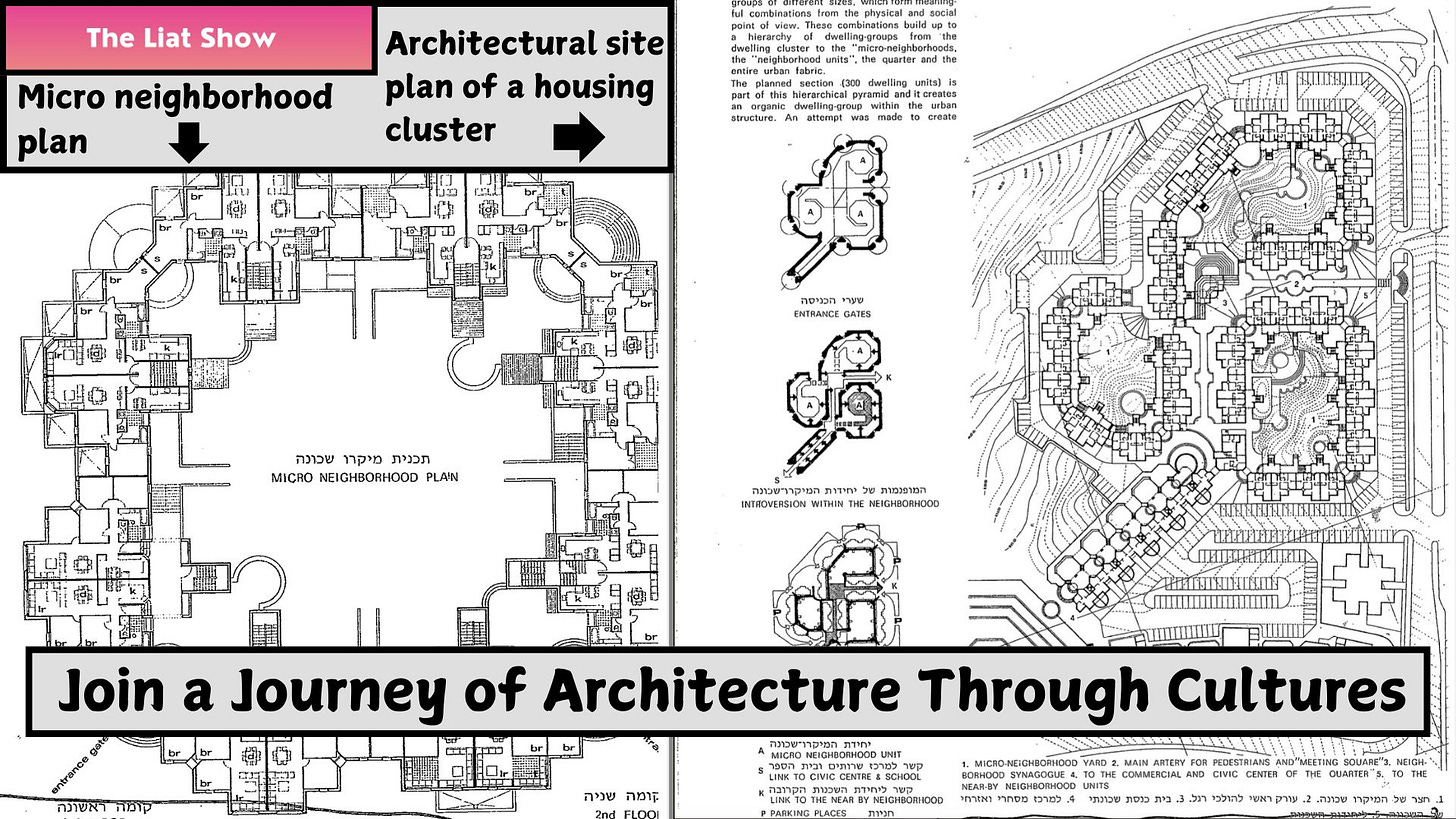

The Sharon Plan was not just about housing. It was about building an entire social structure. Public housing projects under this plan featured three or four story buildings arranged in long, narrow rows. Ground floors were usually elevated, with communal spaces underneath. Most families lived on the upper floors. The buildings were designed for speed. Prefabricated materials were produced in factories and transported to the site. This cut construction time in half. Some buildings were completed in just one year.

But the housing was only part of the vision. The plan included full neighborhood layouts with schools, parks, libraries, commercial centers, and employment zones. Some areas were fully built. Others remained incomplete. Parks were sometimes missing. Commercial centers were often delayed. Still, the idea was clear. These towns were designed to be self-sustaining and to support integration, employment, and long-term growth.

Economic Difficulties and Material Shortages

The economic challenges Israel faced in the first years included a lack of foreign currency, difficulties in importing building materials, and inflation. These difficulties affected both the pace and quality of construction.

A shortage of cement and iron posed a major challenge. The government took several steps to address the shortage, including establishing local production plants and importing raw materials from various countries. The government addressed these challenges through centralized planning, resource allocation, and developing local industries to produce building materials.

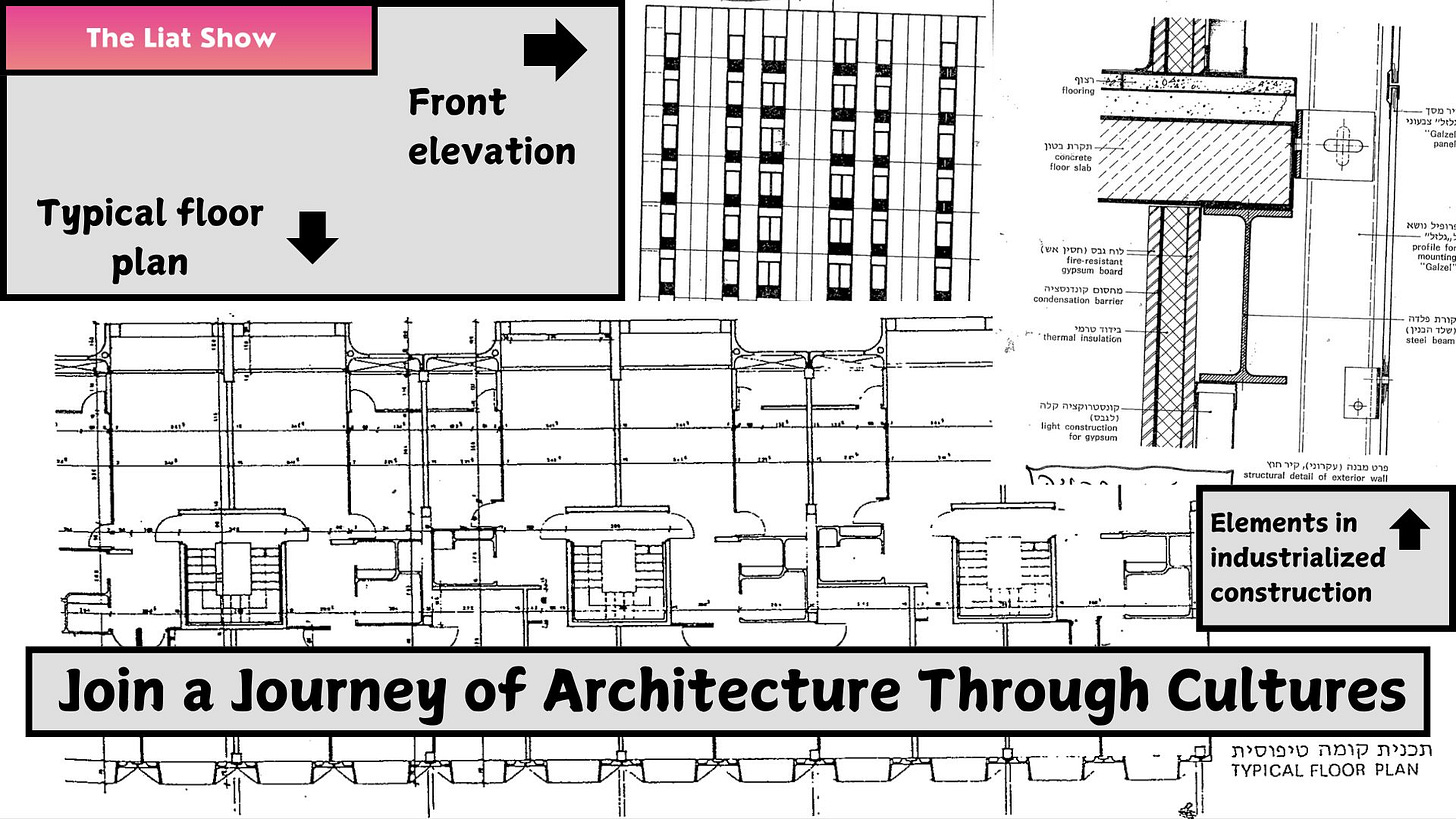

The public housing projects that were designed to provide a cheap and rapid solution using industrialized construction methods were meant to be large residential complexes to house hundreds of thousands of immigrants.

One creative solution that emerged was the use of prefabricated construction methods, which involved manufacturing concrete walls and ceilings in factories and transporting them to the construction site for rapid assembly. This method allowed for the swift construction of buildings without the need for prolonged manual labor on site.

Economic Solutions and Raw Material Imports

To address the shortage of iron and wood, the government used alternative materials such as hollow concrete blocks and relied on local production of raw materials.

Some of the measures taken included subsidized imports. The state signed agreements with various countries, including Germany, under the Reparations Agreement, which helped finance building materials. Establishment of cement and block factories. Factories like Nesher, which was established in 1924, were extended to produce cement locally, reducing reliance on imports. Lastly, Israeli architects and engineers developed structural solutions that conserved building materials, aiming to make the construction process efficient.

Liat: Was that their definition of efficiency? Delivering housing solutions that are half-built?

Nissim: The hardships and disparities of living in the Maabarot were so difficult that people agreed to move into buildings that were still under construction rather than stay there. The government focused on quantity over quality. The urgent need to provide shelter for hundreds of thousands of new immigrants meant they focused on building as many housing units as possible, as fast as possible. That left little time or money for all the other things that make a neighborhood livable.

Liat: If people were willing to move in under those conditions, how come they carry these emotional scars to this day? And why do the second and third generations carry those scars too if it was their parents who made the choice?

Nissim: Development towns, especially in peripheral areas, were largely populated by Mizrahi immigrants, while wealthier or more politically connected communities received better services. This structural discrimination contributed to unequal implementation of Sharon’s vision. These social gaps and inequality still echo, and because the Mizrahi immigrants didn’t know how to present their difficulties and advocate for themselves, they were left with a baggage of psychological burdens that exploded through the second and third generations of these immigrants. This radioactive explosion keeps polluting Israeli society, and these people are on a vendetta voyage or journey of revenge against all government institutions instead of fixing the damages caused by poor execution and lack of accountability for the mistakes during that time.

Liat: Why didn’t the government implement the other elements of these urban plans? Why weren’t schools, parks, commercial centers, and institutions built for the public?

Nissim: The planning process was highly centralized. Local communities had little input, and this top-down approach often led to neighborhoods being built without understanding or responding to actual needs on the ground. The idea of holistic neighborhood design was there in theory, but poorly executed. Additionally, the economic constraints directly impacted every decision the government made. Israel was facing severe austerity. With no foreign currency reserves, high inflation, and a flood of immigrants, the government had to prioritize basic survival needs, mainly housing and food. Budget limitations meant that once apartment blocks were built, there was little money left for supportive services like schools or libraries.

Liat: Now you justify the government for its decisions, but on the other hand, you carry this psychological burden too. How come when you look at this time from a professional perspective, it makes sense, but when you look at it from your personal life journey, you are angry and carry these scars to this day?

Nissim: Because we cannot ignore the political shifts and changing agendas of each party. As Israel’s leadership changed, so did priorities. Urban development plans were disrupted, abandoned, or modified over time. Some areas were simply forgotten after the basic housing was delivered.

Liat: So how come Mizrahis are still complaining about the mistakes the governments made in the first decade, but all the other governments haven’t done anything to fix these mistakes?

Nissim: You ask important and wise questions. Looking back and analyzing from a perspective is different than living through it and seeing that other people make progress while other communities are left behind.

Let’s summarize this session. While the Sharon Plan had a comprehensive vision, the combination of economic hardship, political shifts, and the urgent need for fast solutions meant that many essential components of urban life were left out or indefinitely delayed. These gaps planted the seeds of long-term social frustration and inequality still felt today. Yes, even by me.

Liat: Okay.

Nissim: It’s heavy, I know. We’ll talk about it in our next sessions. That is why it’s important that you keep inviting your friends to class. Especially all the entrepreneurs in the construction industry. They need to understand that innovation in construction is not just new materials or a faster urban planning and building construction approval process. It’s a holistic solution that requires looking at 360 degrees of public needs, and when even one criterion is missing, there is an impact on society and the people living there.

Please fasten your seatbelts and subscribe.

Unlock my potential to write the next great chapter in the most extraordinary story ever told. Your support would make a big difference in taking this journey to the next level.

Follow me on My Journey to Infinity to find out. It will be more beautiful than you could ever imagine.

Liat

In this journey, I weave together episodes from my life with the rich tapestry of Israeli culture through music, food, arts, entrepreneurship, fiction, and more. I write over the weekends and evenings and publish these episodes as they unfold, almost like a live performance.

Each episode is part of a set focused on a specific topic, though sometimes I release standalone episodes. A set is released over several days to make it easier for you to read during your busy workday. If one episode catches your attention, make sure to read the entire set to get the whole picture. Although these episodes are released in sets, you can read the entire newsletter from the beginning, as it flows smoothly, like music to your ears - or, in this case, your eyes.