Israel's Bold Gamble: Welcoming a Million Immigrants Amidst Uncertainty

A Story Unfolding Across Timelines.

Current Time.

A Quick Recap

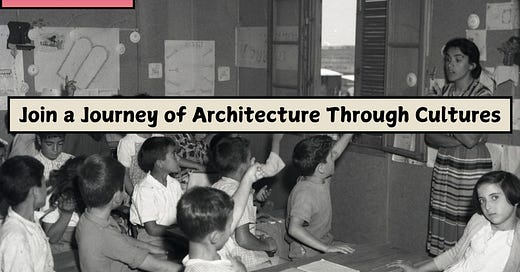

In this series, I am sharing my conversations with my father and inviting you to be part of them. This new installment will focus on the pre-state period and the early days of Israel when the country faced the challenge of housing almost a million immigrants who arrived with nothing but the clothes they wore.

In this installment, we'll focus on the development of large-scale residential projects. We will look at how they were built, what made them possible, and how they shaped the lives of the people who lived in them.

Let's dive into today’s session.

Nissim: We finished our last session with Ben Gurion’s Mission Impossible, remember?

Liat: Yes, absorbing about a million immigrants to a newborn country with no money, no resources, and no structured plan to do so.

Nissim: Indeed, while the new government was building the country’s institutions and operational structure, an influx of Jewish immigrants, most of whom were refugees, flooded Israel. The infant country did not have the means to absorb all of them, but despite that, David Ben-Gurion made a courageous decision that impacted Israel for generations ahead.

He saw the survivors of the Holocaust and the influx of refugees from Muslim countries. He received reports about the unrest brewing against Jews in Muslim countries and the danger looming over them. Israel's leadership understood that it was only a matter of time before massive, violent attacks against Jews would begin, and they were living on borrowed time. Therefore, the decision to accept any Jew who wished to immigrate to the State of Israel was comprehensive despite the many difficulties involved in mass absorption. In contrast to the refusal of countries to accept Jews during World War Two, David Ben-Gurion agreed to welcome any Jew who chose to come to the State of Israel. This leadership act was the most crucial decision any prime minister has ever taken and is still remembered as the most important one in the foundation of the country.

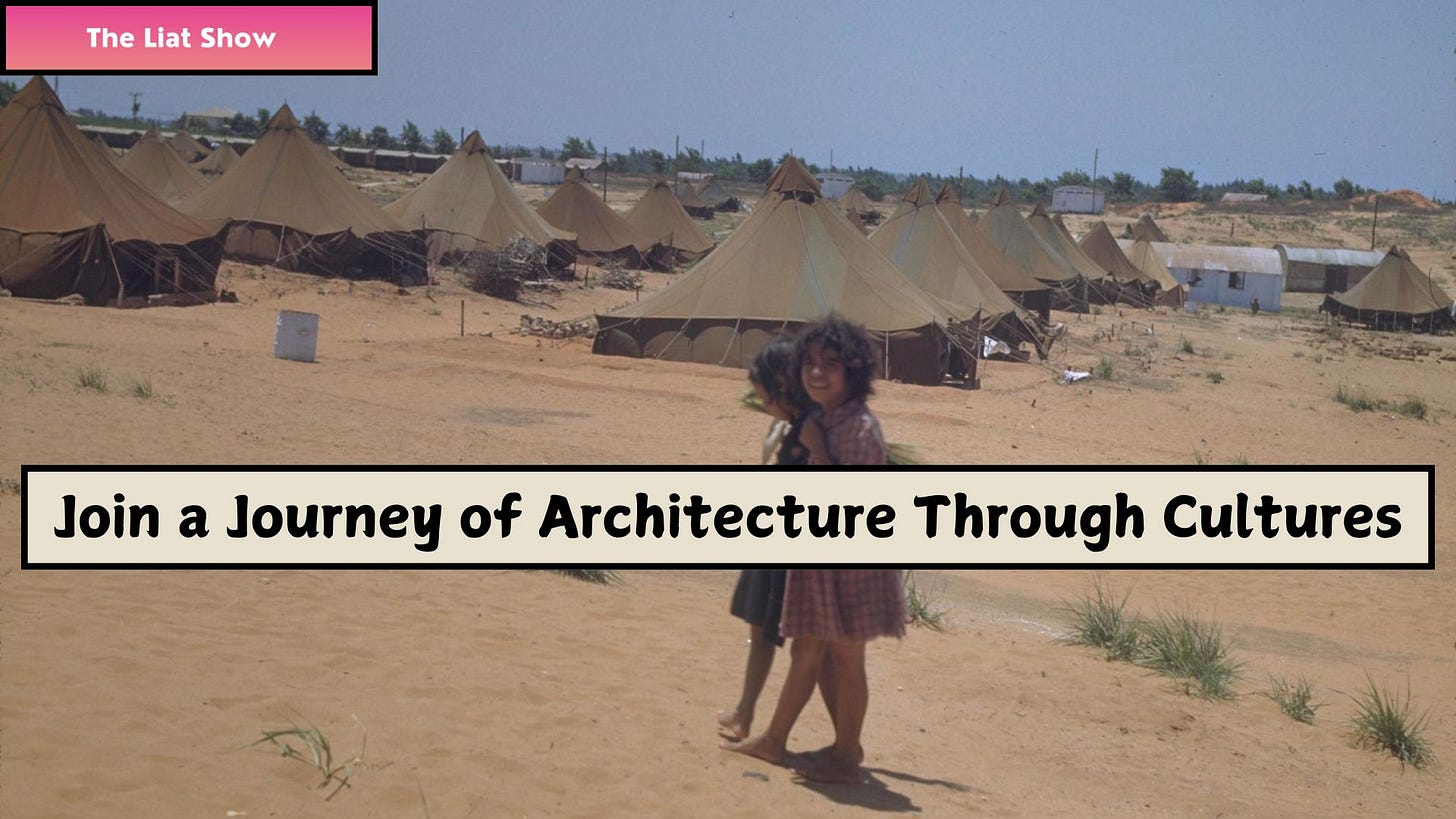

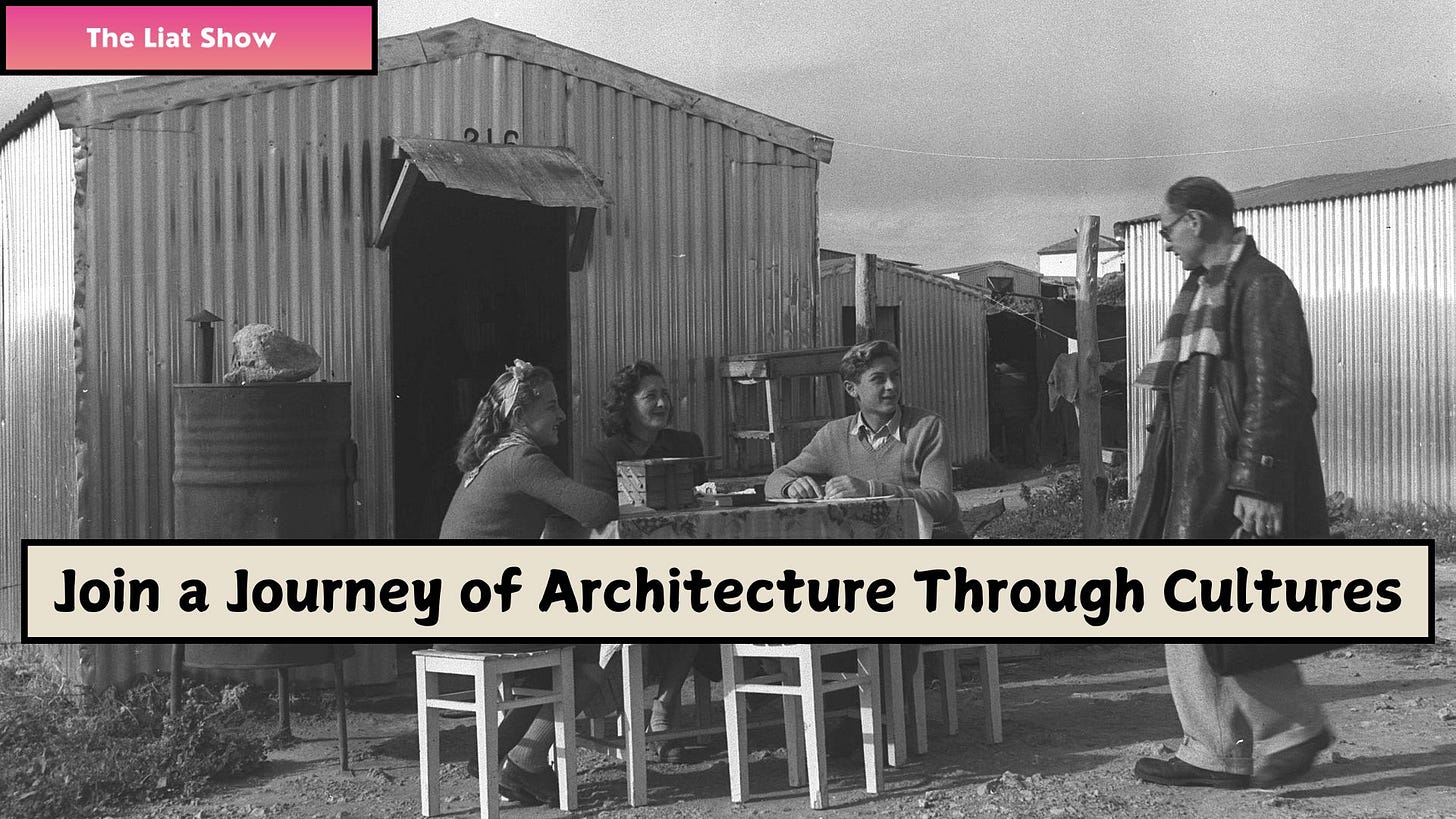

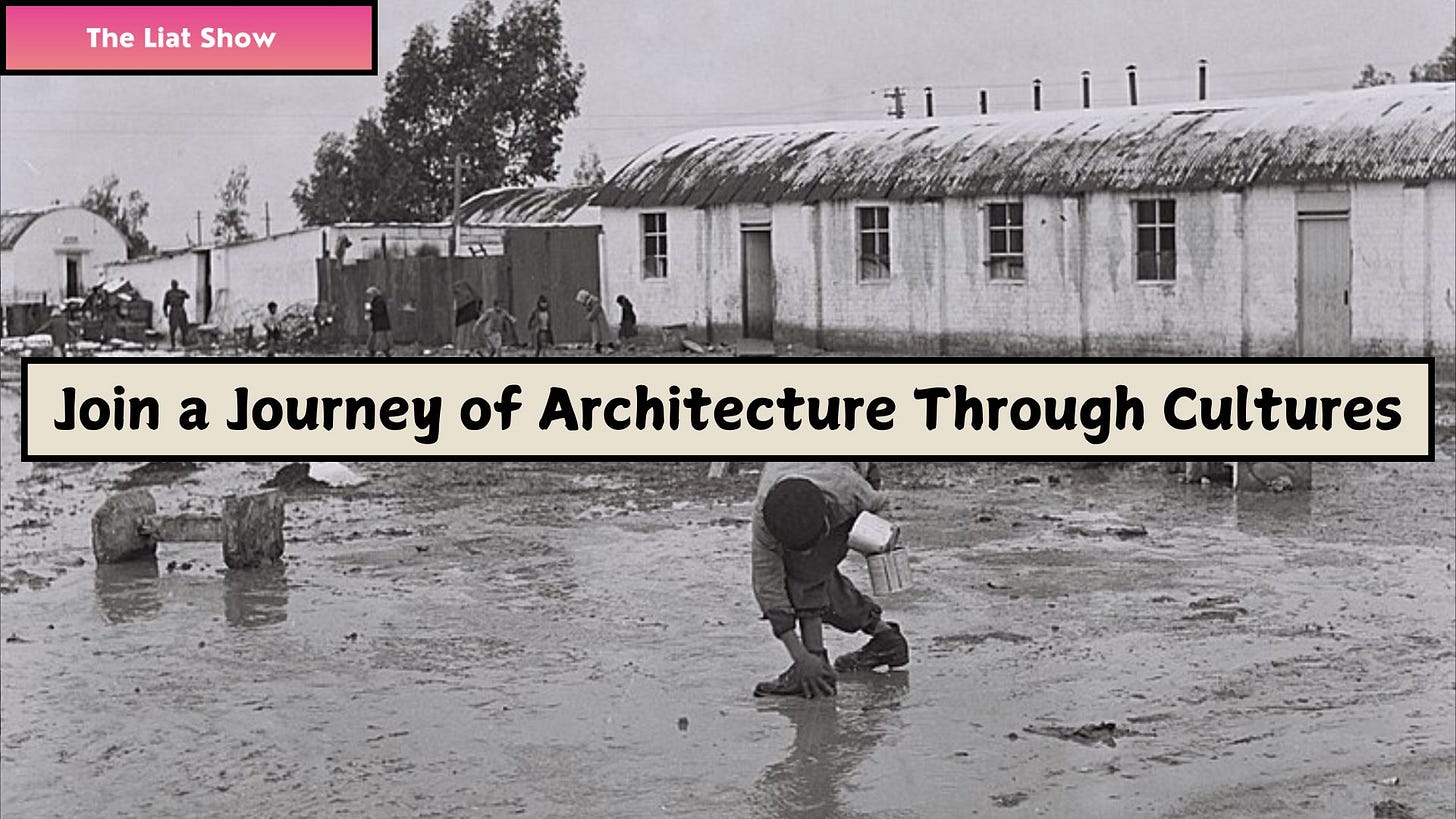

The flood of immigrants forced the government to take many drastic decisions to absorb them and maintain the stability of the country. The immediate challenges were feeding and housing all these immigrants. To house almost a million people required using any solution available to meet the demand. Initially, housing solutions were improvised with what was available, including abandoned buildings, temporary housing units, and the establishment of transit camps to bridge the gap. However, it became clear that these solutions were insufficient, and the state began planning and building new residential neighborhoods.

The need for fast housing solutions led the government to implement an economic plan and austerity policies, along with investing in essential infrastructure to build new neighborhoods, towns, and factories, pave roads, establish education and health systems, and develop industries to provide employment. These efforts aimed to keep Israel’s economy stable, prevent starvation, and provide the essentials to sustain life.

The Eshkol Plan

As waves of immigration intensified, Levi Eshkol and the institutions under his leadership realized that the existing housing solutions could not solve the crisis. Nor could they address the growing unemployment among immigrants, which in turn encouraged economic dependence on state institutions. British army camps and new immigrant centers quickly became overcrowded. The costs of maintaining them, including administrative expenses, were skyrocketing and burdening the young state's limited budget.

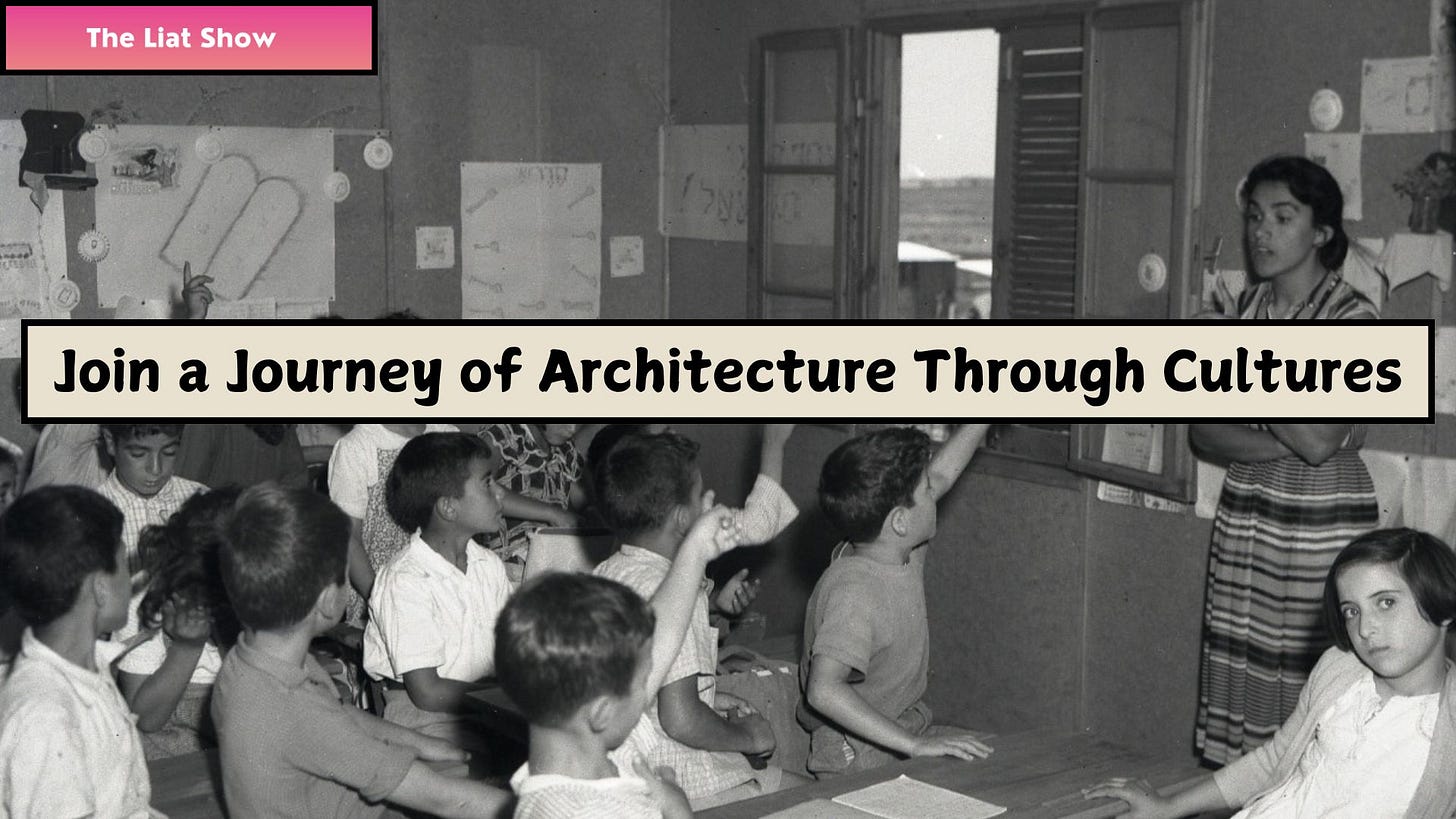

Eshkol proposed a new plan. Immigrant neighborhoods would be established near existing towns. His idea was to create a new kind of settlement, later named Ma’abarah. The goal was for immigrants to live close to established towns, find work nearby, and eventually integrate into the existing community. This would reduce financial dependency, encourage employment, and lower costs. Additionally, placing these communities in peripheral areas would support population dispersion, which contributed to national security.

The plan was quickly implemented. By May 1950, the first Maabarah had already been established in the Jerusalem Hills. The earliest documented use of the word Maabarot appears in a letter Levi Eshkol sent to the Council of the Judean Hills on April 21, 1950.

Most of the Maabarot were located within or near cities where employment was accessible. Others were built where existing infrastructure could support them, including former immigrant camps and Arab villages. A third category of Maabarot was built at new settlement points, such as Dimona, Yeruham, and Kiryat Gat. These were intended for residents to help build the future permanent towns.

In March 1950, under immense pressure on the Agency’s budget, Levi Eshkol offered what was considered a revolutionary proposal. His idea was to make immigrants independent of the Jewish Agency. He aimed to provide them with housing and employment and position them to integrate into Israel’s towns and villages.

Maabarot were not intended to be permanent homes. They were a bridge. A way to place immigrants quickly and affordably, near the labor market, while the government worked on longer-term plans. They were one of the largest public projects the State of Israel undertook to implement its housing and social policies. By 1951, there were 127 Maabarot, housing 250,000 Jews. Seventy-five percent were Mizrahi Jews. Fifty-eight percent of all Mizrahi immigrants up to that point had lived in a Maabarah, compared to just eighteen percent of European Jews.

Maabarot differed from earlier immigrant camps in one fundamental way. In the older camps, residents were supported by the Jewish Agency. In the Maabarot, people were expected to find employment and support themselves. This shift reflected both an economic necessity and an ideological goal.

While the Maabarot served their purpose as a transitional phase, they exposed the deeper infrastructure challenges Israel faced. It was not enough to place people in huts. Roads had to be built. Schools, medical clinics, and job training centers were needed. The planning division’s main task was now massive. It had to house hundreds of thousands of immigrants, build factories, pave roads, and design new towns from scratch.

This brings us to the next critical layer, the harsh economic reality during the 1950s, also known as austerity, Tzena in Hebrew.

Liat: People talk about this time to this day. Even though I mention it in the context of shortage or poverty, though I never lived during that time, it was almost 20–30 years before I was born.

Nissim: True. Even though I didn’t live in Israel at that time. We arrived in Israel from Morocco only in the 1960s. However, your grandparents on your mother’s side, who came from Algeria, lived in Israel during the austerity years. It was a difficult time to live in.

Liat: I bet.

Nissim: Yes, it was. And we will dive into it in our next session. So tell your friends to come on time. We need to get back to the routine of daily classes.

Liat: Last year, I still had a LinkedIn schedule for daily activities. The only activity that is still active is the Lunchtime Flashback with the Daily World War News from the Past every day at noon (PST), where I write about the significant historical events of World War II that happened on that day. It took me almost two years to teach my LinkedIn followers about this schedule, and today there are followers who wait for this post every day.

I want to do the same with The Liat Show episodes. I want to plug it into people’s routines like an alarm clock, in which they know to check their Substack every day at 8 a.m. for the morning class session of The Liat Show, which could be a written one or a podcast, and check their LinkedIn at noon to read the daily World War II news. I want to build a schedule across platforms.

Can you help me do that?

Nissim: Me? How? What do I need to do?

Liat: Just share the schedule with your followers and invite them to buy a ticket to my show. It only costs $8 a month. Help me sell tickets to my show. I want it to be the biggest show in the world. Invite anyone you know to join us. It will be more beautiful than they could ever imagine.

Please fasten your seatbelts and subscribe.

Unlock my potential to write the next great chapter in the most extraordinary story ever told. Your support would make a big difference in taking this journey to the next level.

Follow me on My Journey to Infinity to find out. It will be more beautiful than you could ever imagine.

Liat

In this journey, I weave together episodes from my life with the rich tapestry of Israeli culture through music, food, arts, entrepreneurship, fiction, and more. I write over the weekends and evenings and publish these episodes as they unfold, almost like a live performance.

Each episode is part of a set focused on a specific topic, though sometimes I release standalone episodes. A set is released over several days to make it easier for you to read during your busy workday. If one episode catches your attention, make sure to read the entire set to get the whole picture. Although these episodes are released in sets, you can read the entire newsletter from the beginning, as it flows smoothly, like music to your ears - or, in this case, your eyes.