Building the Future: Lessons from Israel's Early Housing Challenges

A Story Unfolding Across Timelines.

Current Time.

A Quick Recap

In this series, I am sharing my conversations with my father and inviting you to be part of them. This new installment will focus on the pre-state period and the early days of Israel when the country faced the challenge of housing almost a million immigrants who arrived with nothing but the clothes they wore.

In this installment, we'll focus on the development of large-scale residential projects. We will look at how they were built, what made them possible, and how they shaped the lives of the people who lived in them.

Let's dive in.

Liat: So, how long will all of you take this heavy mental weight with you? How long do people want to keep living these feelings of humiliation and discrimination? How many generations will need to suffer until we all let go and start building the future?

History is filled with tragedies, atrocities, disasters, and mistakes. It’s crucial to study it, learn from it, forgive, and move on. How many generations will keep holding on to bitterness, preserving resentment and a sense of revenge instead of moving on with their lives?

Why can’t we say to ourselves that we learned history, we have learned about our own family past, but it's about time to let it go because none of that happened to me. All these are stories that I’ve known since childhood, but they were never during my time. Everything was 10 and sometimes 20 or 30 years before I was born. So I’ve learned from history, but I cannot get stuck in the past, in a time before I was born. It's about time to let go and release this energy from us.

Nissim: I doubt that could ever happen. These people were brainwashed since infancy with hatred. They are brainwashed in the same way terror organizations teach their kids to hate. Same methods, same tools.

Their level of hate is enormous. That revenge toward specific groups in society is much more important to them than rebuilding, fixing, or creating. This urge is more powerful, and they cannot control it.

However, with all the mistakes that were made, most of them were babies or kids and didn’t understand the full atmosphere from a grown-up perspective. So we, and especially those who heard personal stories but weren’t aware of the political, economic, cultural, security, or health atmosphere at that time... so let’s remember some of this history.

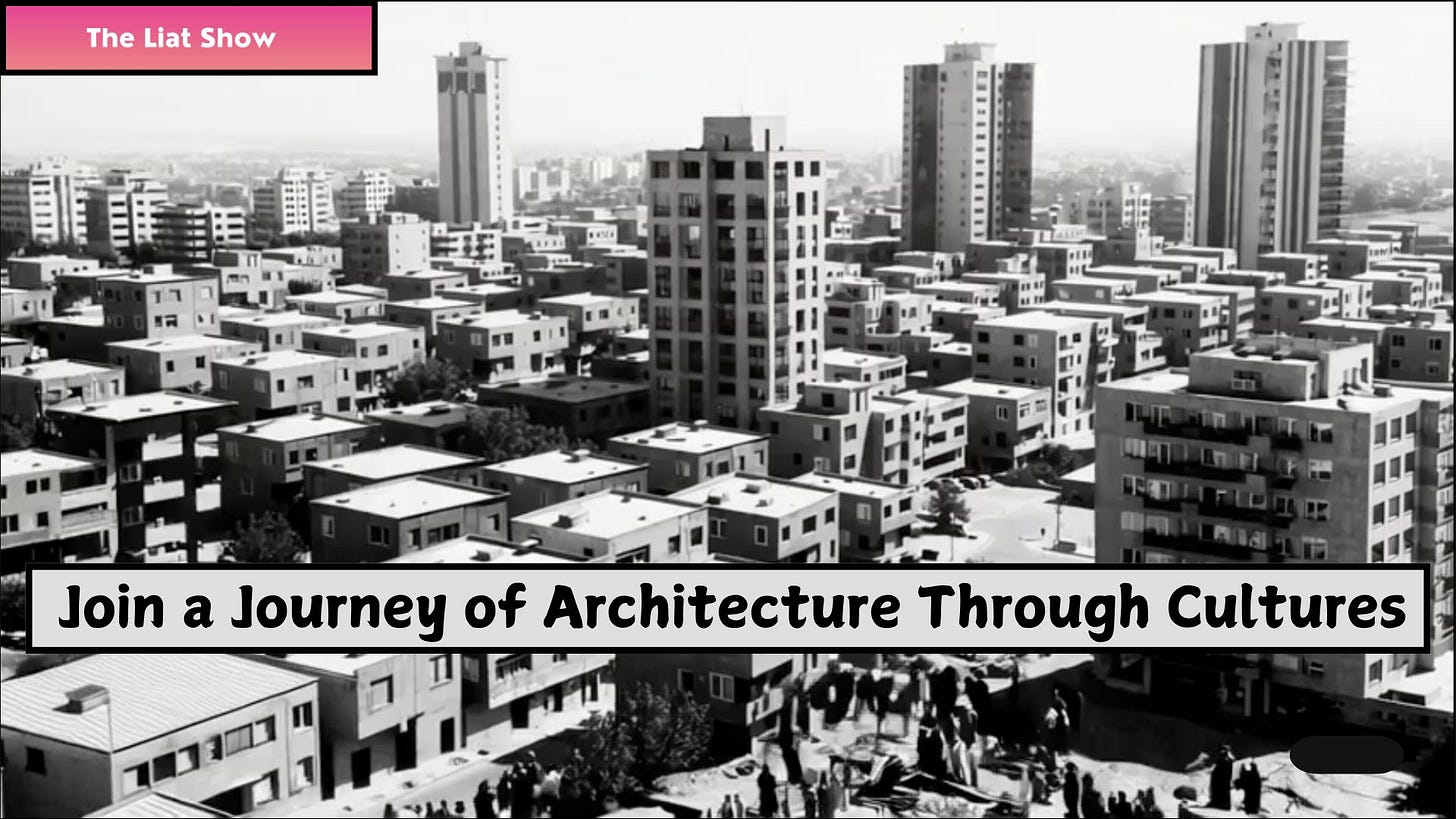

The Impact of Immigration on Urban Planning

The large waves of immigration also influenced urban planning in Israel. New cities were established, and new residential neighborhoods were built in existing cities. The design of these new cities was based on modern planning principles, taking into account the social and economic needs of the population.

Despite its phenomenal achievements, Arieh Sharon’s national plan had many mistakes. Criticism of it could only be analyzed based on historical analysis and later assessments rather than during the years it was implemented.

The main arguments for criticism focus on the overemphasis on speed over quality. The plan prioritized rapid construction to absorb the massive influx of immigrants, which led to poor building quality, lack of insulation, and minimal comforts in many housing units.

The uniformity and lack of cultural sensitivity in the planning model assumed one-size-fits-all solutions, with minimal consideration for the cultural diversity of immigrant populations, especially Mizrahi versus Ashkenazi communities. This contributed to alienation and social tension in many development towns. Many new towns were built in remote or peripheral areas, like the Negev and Galilee, without sufficient infrastructure or job opportunities, which isolated immigrant communities and hindered economic integration.

Moreover, though neighborhoods were designed to include schools, parks, and commercial centers, in reality, many of these public services were delayed or never fully developed, leading to long-term socio-economic gaps. The plan did not sufficiently address employment development, particularly for the diverse skill sets of new immigrants. Many towns lacked local industry, which forced people to commute long distances or remain unemployed.

The Sharon Plan was an emergency response, and as such, it lacked a comprehensive long-term vision. Urban expansion was often random, leading to later difficulties with infrastructure, transportation, and sustainability. The planning process was centralized, with little local or community involvement. This disconnected planning from residents’ real needs and reinforced inequality between the center and the periphery.

These mistakes did not erase the achievements of the Sharon Plan, but they shaped many of the urban, social, and economic challenges that Israel still faces today in terms of development gaps between regions and communities. The resentment from the second and third generations of immigrants who were housed in these neighborhoods and development towns remains to this day. The sense of victimhood among those who lived in those neighborhoods as children and came into power in local and national politics emphasized revenge rather than fixing problems for the benefit of the residents of these development towns today. This cycle of vengeance only polarized every aspect of life.

This first decade was full of mistakes, improvisation, and learning on the job. But it was also marked by bold decisions, creative planning, and an unshakable belief in the future. Israel’s leadership knew they were building under fire, with limited means and urgent needs. But what they managed to create laid the groundwork for a functioning country.

Liat: I’m sorry, but the problems of bad urban planning or poor execution of urban plans are not unique to the State of Israel. Similar problems led to similar outcomes in many other places around the world. So why do the people who lived in those neighborhoods want revenge in everything instead of trying to fix the problems? People living in similar projects in other countries faced the same issues, so why do they act differently?

World Criticism

Beyond the political climate in Israel and accusations of discrimination by the residents of these public housing projects, we can see similar outcomes in many other countries around the world. So it seems that this pattern was not unique just to the State of Israel. Despite discrimination and bias among people in Israel, similar outcomes of poverty and crime are evident around the world. When the result is similar, it raises a question about the core problems that led to these outcomes in different geographical locations, cultures, religions, and government systems.

This indicates the necessity for holistic planning of a neighborhood, city, or any new form of settlement. Constructing residential buildings or even private villas on a large scale is inadequate if planners do not consider all other aspects of life, particularly employment. Each neighborhood requires commercial spaces for grocery stores and essential products within a reasonable distance. Furthermore, access to nature, such as parks or forests, is significant. A neighborhood also necessitates a library, accessible government offices, public transportation, schools, kindergartens, services for the elderly, and entertainment options like movies and theaters. Without these, neighborhoods are unhealthy and tend to decline.

For the new cities along the borders, such as Kiryat Shmona and Beit She'an, one of the primary goals in establishing them was to secure Israel's borders. Security reasons led to the establishment of new towns and the construction of residential building projects in them. While the government was focused on the housing projects, all other aspects of life were sorely lacking, especially employment. This resulted in social unrest and an explosive social charge filled with resentment, hate, and bitterness toward Israel’s leadership and institutions. This emotional baggage stemmed from the poverty and financial hardship that the residents of these development towns, new cities, and neighborhoods still endure.

Conversely, these communities often lack an entrepreneurial spirit or incentives to work because their parents did not work at all. Ultimately, generations of children learned from their parents to constantly complain but not to take action to improve their situation and their children’s lives.

Lessons Learned

What I can see clearly is that innovation in construction or the goal to complete construction projects fast are recipes for cultural, social, educational, and economic failures. Providing housing solutions, even for free, without proper education, health, and governmental functional systems for the citizens destroys the social fabric and harms society rather than benefits it.

Urban planning is essential and must involve not only city planners, architects, infrastructure professionals, and transportation experts but also professionals from the education, health, commerce, employment, and culture sectors. Without seeing the whole picture, the overall solution remains incomplete. Partial solutions are a socially explosive time bomb likely to detonate across generations when residents compare their social and economic progress to that of more developed cities.

On the other hand, the lack of housing solutions and the lengthy approval process for establishing new housing projects also harm society and lead to social unrest, which further damages the social fabric.

So what we need to do now, these days, is fix or better plan neighborhoods, housing projects, residential buildings. Why can’t we learn from the past and teach the people? Currently, only urban planners, architects, and civil engineers know that as part of their academic education. These professionals also understand the impact of every single aspect missing from the complete plan from their experience. But the public doesn’t know the theory because they never learned it or its effects on reality. The public feels and needs to deal with the outcome at the end of the chain of failures, but they don't know the causes of what impacts their lives.

Nissim: Basically, you are right. Nobody has ever thought of teaching the public what a good urban plan should include and what bad execution looks like, and its direct effects on their lives. We need to teach the residents what they should have in their communities. Then it would be their responsibility to make sure all elements are there, and they get what they should.

Most people have no idea what the brown areas on the map actually mean. In Israeli urban planning, the brown color represents public buildings, like schools, kindergartens, community centers, synagogues, cultural institutions, and health clinics. It doesn’t mean green spaces or parks (those are marked in green). The number of public facilities, including things like fire stations or medical services, is supposed to be planned according to the size and needs of the population in that neighborhood. But when these things are missing or only partially implemented, the public stays silent. And that’s a problem. The community deserves to have all the people and services needed to live a normal life.

You are right. The solution must come from the people. If the public wants to learn its rights, they have to learn to bridge their knowledge gap in the construction and real estate markets. The public must learn how their community should function and what services the public deserves to receive. If we start with the people, it would be much easier to implement housing solutions even in the near future.

Liat: Today, we see the same problems and difficulties in the current housing crisis. The shortage of new housing projects leads to an increase in prices without correlation to the minimum and average wages in the market. On the other hand, we see a rise in innovation in construction, from materials to construction methods, that drastically reduces the project time. However, these innovative methods are being implemented too slowly in the market.

Nissim: Because the personnel on the ground, the people who dirty their hands and do the hard job, are the last to learn about innovative construction methods. The work manager or contractor doesn’t want to take responsibility because of a lack of experience with these innovative methods and doesn’t want to get sued, so what happens in practice is that the majority of the construction workers throughout the entire construction process are using archaic methods.

Instead of teaching the workers on the ground to implement new methods, the focus is to increase awareness and sell these solutions to the project developer or the real estate owners. Who couldn’t care less because they are not the people who will populate these houses or residential buildings. Most of the construction workers are working in small groups, and they are spread across wide geographical locations, which most of the time do not overlap.

All we need to do is teach these workers at construction sites or even online. Let them experiment with innovative materials or tools. Suppliers and companies should support the contractors and workers on the ground and let them know that they have your support. Workers need to know you have their back. Innovative companies should teach workers on the ground how to use new tools and materials. Help them fund new tools or give them a payment plan, but either way, let them lead the market because without their ability to learn innovation, we’ll never fill the housing gap.

We must speed up; however, the only way to speed up is through education. We have to teach the public what they deserve to receive as residents and citizens of their community, and we must teach the workers on the ground in the construction industry innovation, otherwise we won’t make it. We have to speed up the capacity of current workers with technology. We must develop a method to teach remotely while being able to experiment and test remotely throughout the education process.

This would be the best course in your school!

Liat: It’s our world school. And yes, these would definitely be essential courses, in plural. Teaching the public is one aspect, and teaching the professionals is the other. But technically, they are complementary.

How come no one ever thought of it? Why did nobody think to teach these basics as part of compulsory education? This is the most important knowledge every individual must know about their environment, neighborhoods, city, state, and country. People have to learn what urban planning is because this is their life. This is what they breathe throughout the day, and this is the reflection of their life in every aspect of life.

Nissim: This discipline holds many subdisciplines. As part of learning how to read urban planning maps, construction blueprints, and plans, students would learn laws, regulations, sociology, history, culture, health, education, entertainment, facilities, institutions, organizations, and their services to the public. At the same time, the public will learn its duties and rights. The public has no idea what it means to be a public. They have no idea what their responsibility is, their role as residents, and what is required of them to do as citizens when supporting or opposing motions, activities, or actions within their community.

Liat: Wow. I love that. I love that a topic interweaves with other topics and provides additional perspective to the course of history. The public can and must learn how to act now from a mature perspective and lessons learned from the past.

The last session in this installment goes over an example of one of the construction companies that built these neighborhoods, and a high-level review of what happened in the US at that same time.

In the next installments, we will explore how the Israeli government recognized its mistakes in these housing projects and neighborhoods. We’ll review the national renewal project for these neighborhoods and how the renewed public housing efforts reshaped Israel’s urban landscape in the decades ahead.

Please fasten your seatbelts and subscribe.

Unlock my potential to write the next great chapter in the most extraordinary story ever told. Your support would make a big difference in taking this journey to the next level.

Follow me on My Journey to Infinity to find out. It will be more beautiful than you could ever imagine.

Liat

In this journey, I weave together episodes from my life with the rich tapestry of Israeli culture through music, food, arts, entrepreneurship, fiction, and more. I write over the weekends and evenings and publish these episodes as they unfold, almost like a live performance.

Each episode is part of a set focused on a specific topic, though sometimes I release standalone episodes. A set is released over several days to make it easier for you to read during your busy workday. If one episode catches your attention, make sure to read the entire set to get the whole picture. Although these episodes are released in sets, you can read the entire newsletter from the beginning, as it flows smoothly, like music to your ears - or, in this case, your eyes.